What is BPPV?

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV) is a common cause of dizziness, with up to 17% of all dizziness presenting in patients are attributed to this condition (1, 2). BPPV causes short bursts of intense dizziness, known as “vertigo” (a feeling like the world is spinning) when the head is placed in certain positions such as lying down, rolling over in bed, looking upwards or bending over.

In addition to Vertigo, symptoms of this condition can include:

- Dizziness or light-headedness

- Nausea and/or vomiting

- Unsteadiness and/or

- Difficulty concentrating or a feeling of fogginess

BPPV symptoms vary from person to person and maybe experienced for very short periods or may last for a long time without treatment.

What causes BPPV?

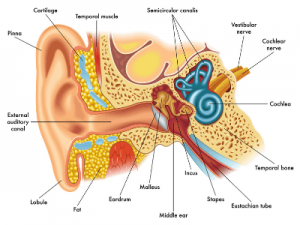

BPPV occurs as a result of a disorder of the vestibular system (the balance organ of the inner ear). The vestibular organs in each ear include the utricle, saccule, and three semicircular canals. BPPV occurs as a result of otoconia, tiny crystals of calcium carbonate that are a normal part of the inner ear’s anatomy, detaching from their normal location and rolling into one of the semicircular canals. When the head is still, gravity causes the otoconia to clump and settle. When the head moves, the otoconia shift and send false signals to the brain, producing a sensation of vertigo. For example, overnight, the calcium crystals often clump together while lying down sleeping and when a person with BPPV goes to get out of bed in the morning, they experience a strong sensation of vertigo.

In people over 50 years of age, BPPV is most commonly ‘idiopathic’, meaning it occurs for an unknown reason, but is generally associated with natural age-related deterioration of part of the inner ear, called the otolithic membrane (3, 4). The most common cause of BPPV in people under 50 is head injury, and is presumably a result of concussive force that displaces the otoconia (5). BPPV is also more likely to occur if suffering from other disorders of the vestibular system including Vestibular Neuritis (inner ear infection) (6), Migraines (7), or occasionally post-surgery (8).

How is BPPV diagnosed?

BPPV is diagnosed based on the description of your symptoms, a thorough medical history, along with specific tests for this condition. One particular test is known as the Dix-Hallpike test and involves lying down whilst the therapist observes your eye movements (called ‘nystagmus’) to determine which semicircular canal is affected by this condition.

How is BPPV treated?

If it does not resolve itself, your therapist can perform specific treatments or manoeuvres (such as the “Epley Manoeuvre”), which are safe, simple and quick in order to resolve your symptoms. To resolve the symptoms, we need to move the crystals back to where they came from. This can be done by moving your body and head through a series of slow, controlled movements. The exact positions will depend on which canal the crystals are in, and whether the crystals are free-floating or attached to part of the ear canal. For most patients, dizziness can be stopped after just one treatment, though occasionally the treatment will need to be repeated a second or third time. Rarely does BPPV require referral for alternative treatment.

Post-treatment recommendations:

After the treatment, it is common to feel slightly unwell or imbalanced, and this generally lasts for around 48 to 72 hours. Following this, if the treatment is successful, you should have no symptoms when in the positions that used to make you feel dizzy.

After treatment is performed, it is recommended that you avoid any aggravating movements for the remainder of the day (For example avoid looking up, looking down or laying down). Your therapist will provide you with a further treatment plan, depending on your diagnosis during your session.

Should you continue to have symptoms after 72 hours, and you have tried any additional recommendations with no resolution, please contact your treating Vestibular Physiotherapist.

Can BPPV recur and what can I do about it?

Unfortunately, BPPV tends to be a recurrent condition, with the recurrence rate being around 30% within the first year after onset of the condition, with most cases involving the same ear previously affected (9, 10). If it tends to be recurrent for you, your Vestibular Physiotherapist can teach you how to self-treat your BPPV with repositioning manoeuvres such as the Epley manoeuvre should you feel comfortable doing so. There is also evidence that Vitamin D can help to reduce the rate of recurrence of BPPV, hence it may be worth having your blood levels tested and supplementing if you are low in Vitamin D (11). Calcium can also be beneficial if the likely cause is related to reduced bone density (11).

If you have any questions regarding your BPPV or its ongoing management, please us at Brunswick Health on (03) 9380 8099.

References:

- Bösner S, Schwarm S, Grevenrath P, Schmidt L, Hörner K, Beidatsch D, et al. Prevalence, aetiologies and prognosis of the symptom dizziness in primary care – a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):33-.

- Parnes LS, Agrawal SK, Atlas J. Diagnosis and management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). CMAJ. 2003;169(7):681-93.

- Hornibrook J. Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV): History, Pathophysiology, Office Treatment and Future Directions. Int J Otolaryngol. 2011;2011:835671.

- Chen L, Bradshaw A, Halmagyi GM. Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo. In: Aminoff MJ, Daroff RB, editors. Encyclopedia of the Neurological Sciences (Second Edition). Oxford: Academic Press; 2014. p. 409-10.

- Kim M, Lee D-S, Hong TH, Joo Cho H. Risk factor of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in trauma patients: A retrospective analysis using Korean trauma database. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(49):e13150-e.

- Balatsouras DG, Koukoutsis G, Ganelis P, Economou NC, Moukos A, Aspris A, et al. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo secondary to vestibular neuritis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;271(5):919-24.

- Kim SK, Hong SM, Park I-S, Choi HG. Association Between Migraine and Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo Among Adults in South Korea. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 2019;145(4):307-12.

- Shan X, Wang A, Wang E. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo secondary to laparoscopic surgery. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2017;5:2050313×17692938.

- Pérez P, Franco V, Cuesta P, Aldama P, Alvarez MJ, Méndez JC. Recurrence of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otol Neurotol. 2012;33(3):437-43.

- Luryi AL, Lawrence J, Bojrab DI, LaRouere M, Babu S, Zappia J, et al. Recurrence in Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo: A Large, Single-Institution Study. Otol Neurotol. 2018;39(5):622-7.

- Jeong SH, Kim JS, Kim HJ, Choi JY, Koo JW, Choi KD, et al. Prevention of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo with vitamin D supplementation: A randomized trial. Neurology. 2020;95(9):e1117-e25.